Wyatt White was born to Abram White and Joanna Hanks White in Greene County, Virginia around 1857, four years before the beginning of the Civil War. Greene County had previously been part of the larger Orange County area. Wyatt’s birth date as shown here is deduced partly from his marriage license recorded in 1879, which lists his age as 21. His race or ethnicity in the 1880 census is recorded as mulatto. “Mulatto” is an outdated term for someone with one black parent and one white parent. This word is now considered to be offensive.

Wyatt White: Birthplace

The area surrounding Orange County, where Wyatt White was born, was inhabited for thousands of years by various cultures of indigenous peoples. At the time of European arrival, the Ontponea, a sub-group of the Siouan-speaking Manahoac tribe, lived in this Piedmont area.

Orange County was formed on 1 January 1734 from the western part of Spotsylvania County. It was named for William IV, Prince of Orange-Nassau, who married Anne, daughter of George II in 1734, the same year the county was created. At that time, Orange County’s jurisdiction included all Virginia lands west of the Blue Ridge as far as the Mississippi River.

In 1783, Orange’s western and northern portions were taken to create Augusta and Frederick counties, respectively. The final subdivision of Orange came in 1838 with the creation Greene County. Since that time, Orange has preserved its current boundaries.

The first permanent settlement of the region occurred in 1714, while Orange was still part of Spotsylvania. Governor Alexander Spotswood imported 13 German families (total of 42 people) from Westphalia to work his iron ore mines at Germanna. Subsequent groups of German workers brought over in 1717 and 1726 swelled this group. Many of these families later moved to nearby counties, eventually spreading throughout the state and the country. (Source: Wikipedia)

The geographical features of Wyatt’s birthplace are diverse. Between the lowlands along the Rapidan River and the highlands of the Southwest Mountains lies a countryside which varies from gently to steeply rolling terrain as it continues westward toward the Blue Ridge Mountains.

The county’s climate is usually described as temperate or modified continental, meaning it is generally pretty nice with a handful of hundred-degree afternoons in the summer and a zero-morning or two in the winter. The worst snow storm is believed to have been the Blizzard of 1857, the presumed year of Wyatt’s birth. (Source: Walker, Jr., Frank S., Remembering: A History of Orange County Virginia, Orange County Historical Society, Inc., 2004)

At some point during his childhood or later, Wyatt was apparently taught to read and write. (Source, 1880 Census Report). He was about eight years old when the Civil War ended and may have participated in the education system described below.

Educating Wyatt

Virginia had long outlawed the education of its enslaved blacks, passing increasingly oppressive legislation in the decades leading up to the Civil War (1861–1865). Although some Virginians had once supported the idea of black education, slave insurrections and rumors thereof had halted any movement toward increased slave literacy. Still, free blacks and slaves continued secretly to share what literacy they had. Clandestine schools operated in nearly every city and large town in the state.

Shortly after the Civil War began, African Americans established and taught in schools for Virginia’s freed people. Initial funding for black schools in Virginia came from the freed people themselves, who managed to pay a fee to their teachers. From 1862 until 1865, Northern groups–both existing missionary societies and new, secular freedmen’s aid societies–organized to send teachers to Virginia and other Southern states; to provide minimal salaries; and to send material aid.

Across the South, the Freedmen’s Bureau helped after the Civil War to educate thousands of black students who otherwise might have been unable to attend school. Wyatt would have been about eight years old at that time. The federal response to education –and Emancipation in general—however, was astoundingly inadequate. The Bureau was not allowed to expend funds on teacher salaries, schoolbooks, or classroom apparatuses. It was limited to encouraging black communities to raise money to purchase land for school buildings, providing building material from abandoned military buildings, transporting teachers to schools, and paying rent on schoolhouses.

Despite these obstacles, enrollment in Virginia’s black schools rose steadily from the opening of the first schools in Alexandria in 1861 to 1870, when the Freedmen’s Bureau ceased operations in Virginia and other states. By 1866, nearly 12,000 students were attending schools across the state; by 1868, 19,000 were enrolled; by 1870, the total was nearly 33,000. (Source: https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/freedmens-education-in-virginia-1861-1870/)

Wyatt in the Workforce

As a young man, Wyatt worked as a laborer in Orange County. (Source, 1880 Census Report). It’s not known specifically what type of jobs he worked between 1880 and 1910 before moving to West Virginia around 1910. The US Census Report for that year lists him as working in a West Virginia coal mine as a car dumper. The move to West Virginia is explored later in this essay.

Prior to Wyatt’s birth in1857, the county’s economy in the 1840s and 1850s prospered with the development of several railroad routes through Orange and Gordonsville. The Orange and Alexandria Railroad and Virginia Central Railroad helped foster a diversified agricultural economy in Orange County, bringing produce and timber to markets in Richmond, Washington D.C., and Norfolk as well as more industrial products. Again, it’s not known which sector of the economy Wyatt worked in as a laborer.

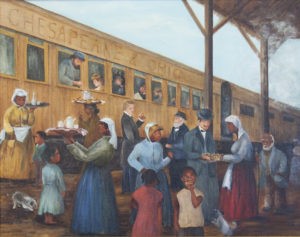

From Slave Labor to Free Enterprise in Orange County: The Fried Chicken Ladies

Enslaved African Americans, who are noted to have probably first come to Orange County in the 1730’s, were employed mostly in the iron mines established by Lt. Governor Alexander Spotswood around the Fort Germanna historical site located in Locust Grove. Later, black labor extended to work on local plantations and in other areas.

Enterprising African American women in the 1840’s earned Gordonsville the title of “Fried Chicken Capital of the Universe” when they greeted arriving trains with baskets of fried chicken and homemade pies balanced on their heads. It’s not hard to imagine Wyatt’s female relatives among these entrepreneurs. The local government began licensing and taxing these women as “snack vendors” in 1879. Their businesses continued until the mid-1900s, when increased regulations became too cumbersome. (Source: Images of African Americans in Culpeper, Orange, Madison, and Rappahannock Counties, by Terry L. Miller, Acadia Publishing, 2019)

When the Civil War ended in 1865, a Freedman’s Bureau was located in the Exchange Hotel in Gordonsville, VA from 1865 to 1868. Wyatt’s parents likely benefitted from such services. Wyatt himself would likely have been too young at age 11 for direct labor assistance from the Bureau, which issued rations and provided medical relief to both freedmen and white refugees.

The Bureau also supervised labor contracts between planters and freedmen, administered justice, and worked with benevolent societies in the establishment of schools. The Bureau worked to make freedmen self-sufficient and to incorporate them into the new free-labor system in Virginia. (Source: National Archives: African American Records: Freedmen’s Bureau)

Wyatt Gets Married

Wyatt married eighteen-year-old Emma White on 3 January 1879. (Source: Virginia, US Select Marriages, 1785-1940). According to those records, Emma was born in Albemarle, VA in 1861–the year the Civil War began. Her parents are listed on the marriage record as Father–Isaac White; and Mother–Heller White. Wyatt would have been about 22 years old.

Emma is shown in the 1880 Census Report as living with Wyatt as his wife. Unfortunately, no further mention of her could be found – not in any subsequent census or death record. Did she die? Did she and Wyatt divorce? Since most of the 1890 US Census Report was destroyed in a fire in 1921, the census records cannot be used to determine if she and Wyatt were still together in 1890 and beyond. Efforts to track her life and time of death will continue.

These questions arise because 15 years after Wyatt married Emma in 1879, according to the 1894 Registry of Marriages, Alleghany County, VA, he at age 37 married again — this time to Lula (sometimes spelled Lulu) Thornton on 20 May 1894. According to the official record, Lula, 22, was the daughter of Charles Thornton and Jennie Thornton. She was born in 1872, according to the marriage record.

Wyatt and Lula remained married for about 16 years, at least until around 1910, the year their last child, daughter Mary, was born. Sometime between 1910 and 1920, Wyatt passed away. The author is still researching the date and official cause of Wyatt’s death, To date, no death records have been found for him. See an undocumented account of Wyatt’s death below.

Puzzling Questions About Birth Mother of Wyatt’s First Son, Phil White

Some puzzling questions arise about the family. Wyatt’s and Lula’s oldest child, Phil White, appears to have been born in 1881 (the date given on Phil’s delayed official birth certificate and which was used to apply for Phil’s social security benefits later in life.) Lula would have been nine years old at the time of his birth. Some researchers, along with Phil’s US World War 1 Draft Registration Record, list Phil White’s birth year as 1884. This would indicate his mother was 12 years old at his birth. This seems more likely.

If the earlier 1881 birth year is accepted, Phil would have already 13 years old when Wyatt married Lula Thornton in 1894; if born in 1884, he would still have been 10 years old at the same of his parents’ marriage. Interestingly, Phil’s birth in 1881 would have been around the last time Emma White, Wyatt’s first wife, can be found in official records (the 1880 census). Was Emma Phil’s birth mother? Was Lula his stepmother, or did Wyatt and Lula simply marry years after Phil’s birth to Lula?

Keep in mind that in 1879, Wyatt had married Emily and according to the 1880 census, he was living with her that year in Greene County. Research suggests Phil was born shortly afterward in 1880 (birth year on Phil’s tombstone), or 1881 or 1884 to mother Lula. Wyatt didn’t marry Lula until nearly 15 years later. It’s not clear if he was married to Emma during those 15 years or if he had been widowed. Even more puzzling is the fact that Phil White’s official birth certificate lists his father as Wyatt, but shows his mother as Lucy Slayer White. Who is she? Is this an administrative error? More research is needed to definitively confirm the identity of Phil’s mother.

The Move to West Virginia: Lure of the Coal Mines

There is little doubt that Wyatt would have moved his family to Slab Fork, West Virginia to work in the coal mines. Like their white counterparts, black miners could make a good living to support their families in this very dangerous line of work.

Coal Mining

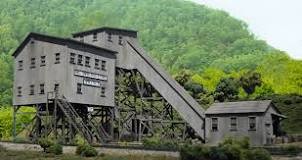

The mine at Slab Fork opened in 1907 and operated until 1983. The town made its mark as an industrial community at a time when coal miners’ families lived in shotgun houses with newspaper-lined walls for insulation and outdoor privies for bathrooms, and sent children to work instead of school so they could survive.

Laborers and their families arrived at Slab Fork in the early fall of 1907. Wyatt was likely among these early arrivals.

Coal in those days was mined primarily by hand — cut with a pick, loaded with a No. 9 shovel, hauled by mules, dumped into a bin and loaded from side chutes into railroad cars. Wyatt’s occupation is identified in the 1910 census as a “car dumper.”

Four-room frame company houses were built, several of which are still standing. Many of the old houses have been remodeled, with additions and updates, including running water, electricity, indoor plumbing and heating systems. Although most company houses were small with only four rooms, a few larger boarding houses were sprinkled throughout the coal camps. Wyatt’s widow is shown in the 1910 Census Report as operating a boarding house Most camps were segregated into white and colored camps and each had their own church but shared a general store, a doctor’s office, post office, and movie theatre.

(Source: https://www.register-herald.com/news/lifestyles/slab-fork-once-bustling-coal-town-forged-bonds-that-live-on/article)

Although it’s not exactly clear what year Wyatt moved his family to West Virginia, the US Census Report of 1910 shows him working in the coal mines as a “car dumper” by then. The census also lists him and Lula as living with three of their children and a boarder in Slab Fork during that year. Phil White, their oldest son–who would have been about 29 years old–does not appear in the 1910 census as a member of their household. (I was unable to locate Phil in any 1910 census.)

Along with Wyatt and Lula, the following persons lived in the family home in 1910:

- Theodore White, son, age 22 yrs. (1888-1960)

- Willie M. White, daughter, age 3 yrs. (1907- TBD)

- Mary E. White, daughter, age 0 yrs. (1910-TBD)

- John Smith, boarder, age 43, preacher

Accidental Death on the Job

Wyatt, who was my great-grandfather, last appears in the 1910 US Census. How and when did he die? While I continue to search for an official record of his death, I remember my father telling me that his grandfather, Wyatt, died when he fell from the top of a coal mining tipple one rainy night and broke his neck. A tipple is a structure used at a mine to load the extracted coal for transport, typically into railroad hopper cars. See image below. This would have been in line with Wyatt’s work as a “car dumper.”

By the time the 1920 census was published, Lula is listed as “widowed” and as head of household. The 1920 census shows Lula living in the family home with her two daughters and six boarders.

|

Household Members |

Age |

Relationship |

|

Lulu White |

50 |

Head |

|

13 |

Daughter |

|

|

10 |

Daughter |

|

|

23 |

Boarder |

|

|

31 |

Boarder |

|

|

30 |

Boarder |

|

|

27 |

Boarder |

|

|

40 |

Boarder |

|

|

29 |

Boarder |

Research will continue in an effort to fill gaps and learn more about Wyatt, his spouses, and his offspring.

(Essay by Dr. Blanche R. Dudley, Great-Granddaughter of Wyatt White, 2022)