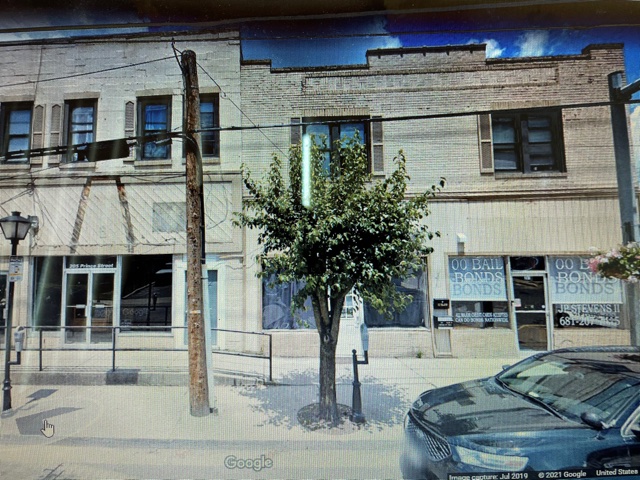

Site of the former Smokehouse (on the right) – 203 Prince Street Beckley, WV

Conversation with Andre White, youngest son of beloved parents Philip “Kid” White, Jr. and Mary Louise Brown White

When I think about Dad and his best traits, loyalty and perseverance come to mind, among others I could talk about. He was all about showing unconditional love to family and community, no matter the circumstances. I remember him working constantly to find ways to provide for us. During the 1950s and 1960s, work was spotty in the coal mines, poverty was all around, and of course, discrimination cast its ever-present pall over Southern WV’s Black coal camps and communities. Folks had to look after one another to survive, relying on resourcefulness, people skills, compassion, and savvy, which Dad had in spades.

Down-to-Earth

Dad’s early life growing up in Stotesbury, WV and surrounding coal camps in the 1920s was definitely humble. He wasn’t born with a silver spoon, and he probably finished school through the tenth grade. But what he had as a young man was special, and some would say he had a personality that was “extra,” making some of the hard work he did throughout his life seem like fun. They say when Dad married Mama, he was “marrying up.” She was beautiful, smart, and had tasted some of the good life that follows education. Mama fell deadly in love with Dad, which is understandable. He had charm and good looks that can only come from the Father. They say some Cats have a charismatic “it,” and that people just always want to be around them. Well, Dad had that “it.” It’s no surprise that us kids got Dad and Mama’s combined traits. Dad put the ”hustle” in us, and Mama instilled in us a drive and desire to learn and succeed.

When Mama passed in 1969, we lived in Raleigh, WV. I was 11 years old. Dad had to manage the five of us kids, with many dreams cut short. The thing I remember most after Mama’s passing is that Dad became all about advancing the family’s legacy. He was determined to see us kids through any situation—all the way through—including his grandkids. He treated his kids’ opportunities and successes as his. He never left us on our own. Whether it was graduations, sporting events, or school performances, he was there, period. He traveled any distance, to any town, to plant the family’s flag—supportive, proud, and worthy of the occasion. I recall in 1989, we drove 12 hours to upstate New York to see my nephew graduate from an Ivy League school. I recall Dad saying something to the effect: “We’re a long way from Raleigh (WV), but these Cats put their pants and belts on the same way I do. Well, I’m here today, and I’m putting my suspenders on!” Dad always represented, looking and feeling sharp doing it.

Dad’s natural way of seeing value in every person and celebrating their unique gifts—regardless of their position in life—was a trait I observed early on and adopted for myself. This trait, no doubt was partly responsible for Dad’s charisma and the fact that a few of his kids, like me, immersed themslves in the field of education, becoming decorated teachers to students of all abilities and from all socioeconomic backgrounds. My first awareness of Dad’s treatment of others came when, as small kids, my maternal grandfather would visibly lose patience with me, and he would be quick to heap praise on my older brother for his ability to learn multiplication tables and school lessons faster than me. By contrast, Dad never put conditions on his love for me or anyone else. In fact, one of the ultimate examples of Dad’s unconditional love occurred later in the early 1970s when he cast aside whatever feelings existed when he married Mama, and he oversaw the care of my maternal grandfather until the end of days, when he could no longer care for himself.

Dignity in an Oft-Ugly Society

I distinctly remember times when Dad needed to be strong and endure for all of us, as a father and a man. I sensed this at a young age and believe upholding Dad’s dignity was a main reason I worked so hard to become a successful athlete. I won dozens of trophies and State-wide recognition in baseball, football, and college basketball. One memory I recall is Dad driving the car from Sophia to Beckley, having to pass Ku Klux Klansmen, who on any other day were regular members of the (segregated) community and some of whom ran local businesses or played on coal camp baseball teams. It’s emotional to this day, remembering that we could not look over at the flames for any reason, but had to endure the open and ever-present racism that surrounded us.

The memory of the Klan’s presence and other indignities made me determined to use sports to outshine the sons of the more well-to-do businessmen and prominent officials in Beckley, especially those who seemed to treat blacks as inferior. I felt at least on gameday, the spotlight and eyes of the town would be on me, and on the family of Kid White. No matter if Dad showed up with no muffler on the car or possibly needing a battery jump, I wanted spectators to see his boy making plays like Sandy Kofax, Bob Gibson, Jerry West, or Bob Cousy. Dad deserved the sense of pride and honor he must have felt, as I watched him talking in the stands with the city’s so-called important men.

My most cherished sports memory, however, occurred when Mama was too sick to leave the car to see one of my Little League baseball games, so Dad parked just beyond the outfield fence. No one knew that day that Mama was closely watching the baseball diamond from the passenger seat, or that my inspired performance came from my sworn promise to her that I would hit three home runs her way. I did just that, to the astonishment of the fans, coaches, and the opposing team. After the game, the ballplayers went for their usual hotdogs and snow cones, but I ran toward Dad’s car as fast as I could for something much more precious to me that day.

Hustler and Go-Getter

I have many memories of Dad’s business savvy because he used it to keep food on the table and a roof over our heads. He was an entrepreneur before entrepreneurship became a concept to us. My earliest recollection dates back to when I was 4 or 5 years old. It must have been a time when there was no work for Dad linked to the mines, because I remember he sold ice door-to-door using his barely reliable car, hawked smelly fish during the summer, and cleaned up a cafeteria and the Smokehouse pool hall in Beckley. In Raleigh, he was the de facto mayor. He was the go-to for bartering everything from green stamps and surplus cheese to moonshine. However, a vital source of income for Dad emerged when he took charge of and became a master of what would now be called a “sportsbook” for a network of individuals and businesses in the area.

Dad’s business dealings were shrewd, sophisticated, and guaranteed profits. He took a 10% cut when clients won; he placed parallel wagers to piggyback on clients’ big wins; and he sometimes bet opposite his clients to hedge losses. To the delight of our sports-loving family and cousins, he often used his profits, or “the man’s money,” to gift us a few parlay cards to play. For other customers, he created his own proprietary numbers games if they needed more action, beyond the ballgames on TV. Dad‘s gift of gab helped him cultivate an impressive customer base from all walks of life. Those connections ensured our family had access to what would be considered rare luxuries in our community—free or discounted goods of every kind, jewelry, medicine, quality cuts of meat, car repairs, and more.

Mentor and Role Model

Dad’s fun-loving personality and work ethic not only improved conditions for our family, but also made him a positive influence on the community’s young black males, who he employed at night to clean up the Smokehouse. Like a Pied Piper, he drove his beaten-down Buick though the streets of Beckley each night, as youngsters bounded out of their houses into his car, frequently accompanied by a wave from their mothers and a shout of “Hey Kid White!” from the front porch. The crowded car rides and the two hours the crew spent at the pool hall provided the boys—including some who would never finish high school—a temporary escape from their opportunity-starved environment and the discrimination they faced during the day. It allowed them to briefly cast off Beckley’s “invisible handcuffs” and exist in a world where “the man” was not involved. They could roam freely through the pool hall, play billiards after finishing the clean-up, put quarters in the jukebox (mostly filled with country music), and eat food that Dad served from behind the counter. Years earlier, that counter would have been off limits to Blacks. I remember some of the older guys crying because Dad didn’t have room for them in his Smokehouse crew.

I can’t say enough about Dad’s impact on the juveniles he employed. He served as a surrogate father to many of them, which was not lost on their mothers. Those moms appreciated how Dad built up their sons’ values, self-esteem, and sense of self-sufficiency through their work at the Smokehouse. Dad respected each of them for their authentic selves. During the drive to the pool hall—or while the boys’ mops swished dirty soap water back-and-forth across the floors of the Smokehouse—Dad validated everyone’s perspectives on Dr. J, Bill Russell, Bill Walton, the best team ever, or whatever non-sports topic that came up (sometimes even about the birds and the bees). Dad didn’t judge whether the boys used proper verbs and nouns, whether they stuttered, whether they were special-ed, whether they were clean or unkempt; it just mattered they were part of the team, getting honest pay for honest work. I think the greatest respect Dad showed the crew was not allowing them to clean the nastiest parts of the pool hall, which he, in his long rubber gloves, always reserved for himself. In all of the fun, there was no illusion that the job was anything other than cleaning up other people’s B.S., including spittoons, urinals, and toilets. Dad’s attitude probably was that he wanted to give the crew a break from the foul tasks they did during the day, in their normal jobs, to support rich people’s ability to work 9-to-5 in comfortable offices.

Trust and Loyalty

I recall Dad getting very upset when there was the slightest hint of theft by members of his Smokehouse crew. He never allowed it to happen. He made it clear that his reputation and the crew’s ability to continue getting paid depended on the hard-earned trust he established with everyone he dealt with—especially his clients and employers in the pool hall’s backrooms, and the many other prominent people in town who enjoyed a periodic taste of moonshine or a parlay card. Dad’s crew understood his rigorous code of conduct, and they probably appreciated that he never seemed to run into trouble with the law, while the crew kept access to places and privileges otherwise unattainable.

One incident occurred when I was between 6 to 8 years old, and it brought home to me why Dad insisted on loyalty and why he valued others’ loyalty toward him. Dad and I were in the car leaving the Smokehouse one day, and we turned into a one-way alley. As we proceeded, an unmarked police car approached us head-on, advancing in the wrong direction. The grimacing White man in the police car began screaming at Dad: “Move your car, move your car!” I looked into Dad’s face and saw an expression of defiance and stubbornness welling up. Terrified, I knew this angry standoff was getting out of hand and ready to end badly for Dad, so I jumped out of the car, ran into the pool hall and yelled to the men playing pool, “Somebody’s getting ready to do something to my Daddy!” After recognizing me immediately as Kid White’s boy, one of the men told me to stay in the pool hall. He grabbed up a pool stick and rushed into the alley to defend Dad. I don’t know exactly what happened next, but the policeman backed down, allowing us to go on our way. I reflect on that incident a lot, about how I wanted to save Dad, about how he had gotten tired of being embarrassed in front of his family, and the esteem in which he was held by those White men in the pool hall. Their loyalty to Dad compelled them to protect him, even by violence had it become necessary. (Dictated to and typed by Kid and Louise’s oldest grandchild, February 5, 2021)